Documenting Dylan

A few weeks ago, I got caught off guard – yet again - by Bob Dylan. Passing some highway drive time with one of those Spotify new release mixes, amid new cuts from Colter Wall and Rosanne Cash, I heard an unmistakable voice from decades ago. Dylan, sounding as tender and tuneful as any acclaimed folkie of today, was singing “You’re A Big Girl Now” with only his acoustic guitar and harmonica. This was not the version I know in my cells from 1975’s Blood On The Tracks.

I listened with new ears, quietly singing along to the sad, succulent lyrics: “Bird on the horizon, sitting on a fence/He’s singing his song for me, at his own expense.” What started as commuter’s surprise became a time tunnel back to the late 1980s when I pored over that album as if it was scripture. As soon as I could safely check my phone, I found this previously unreleased version of the song had just come out on an official bootleg recording called More Blood, More Tracks, the fourteenth volume of Columbia Records’ official Dylan bootleg series. Its six CDs include all the surviving tape, with multiple takes, studio banter, false starts and rehearsals. When it comes to Dylan, there is always more.

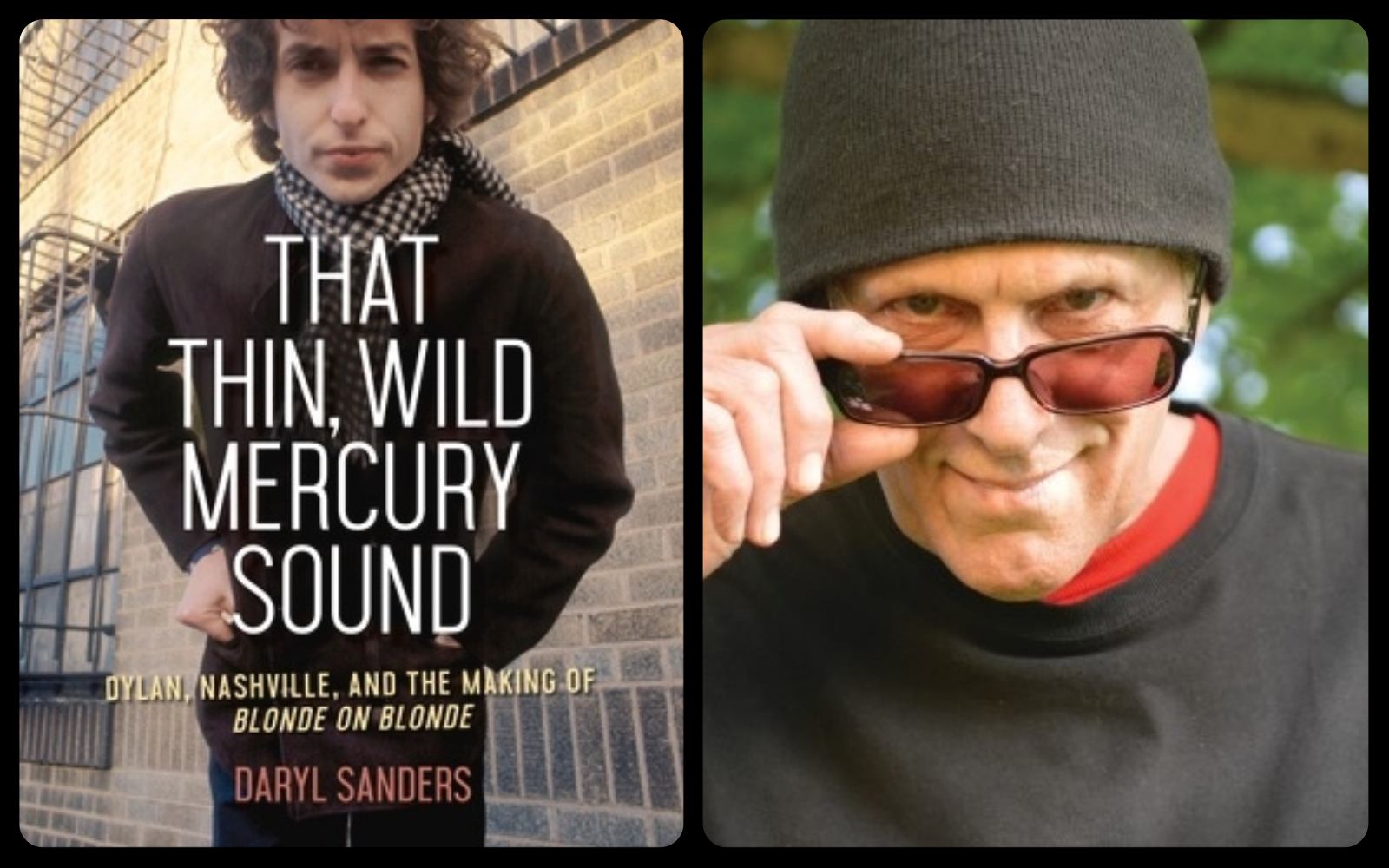

That makes two new chances to bear virtual witness to historic Dylan recording sessions and his creative process, because in October, Chicago Review Press published That Thin Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, And The Making of Blonde On Blonde by veteran Music City journalist Daryl Sanders. In this comprehensively researched and compulsively readable history, Sanders describes a kind of fated collaboration and chemical reaction between the most famous songwriter in the world, then in a rush of creative reinvention, and a crop of ace studio session musicians from Nashville. While the story was told impressionistically in the 2015-2018 exhibit Dylan, Cash and the Nashville Cats at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, the book offers the first character-rich narrative about an album that’s proven as pivotal and enduring as any ever made. Robyn Hitchcock, who appears along with Sanders in the new episode of The String, is quoted in the book as calling the opus the “alpha and omega of rock records.”

It was a rock and roll record but also, because Dylan made it, a folk record and, because of the skilled but loose Nashville vibe, a roots record too. Thus for some, Blonde on Blonde is a founding document of Americana. Bands like Jason Isbell’s 400 Unit are configured with almost exactly the same instrumentation as this Dylan-Goes-Electric era. Sanders argues as perhaps his central thesis that the Nashville Cats – chiefly Charlie McCoy, guitarists Wayne Moss and Mac Gayden, pianist Hargus “Pig” Robbins and drummer Kenneth Buttrey - lived and loved the same roots that lit Dylan’s fire as a teenager. They played on some country sessions for sure, but they were really the city’s top players for soul, R&B and rock, which the first generation of Opry-inspired pickers weren’t so good at. Dylan and the Cats were from different worlds as men, but they were of the same generation and both in the thrall of Chuck Berry, Little Richard, the blues and the sounds crackling across the nation from R&B pioneer WLAC in the 1950s.

“In many ways they were more intimate with that music than Dylan was,” Sanders writes. “They were from the South, so they were closer to the source; it was an expression of their culture, it was in their blood.” And, he notes, they were all highly skilled, versatile, patient, unimpressed by stardom and great listeners. “They were ready and able to take Dylan wherever he wanted to go.”

The linkage and the lure to Nashville came from two guys: Dylan’s new record producer Bob Johnston and multi-instrumentalist and all-around musical mastermind Charlie McCoy. Johnston invited Charlie to a New York session to meet Dylan, where he wound up playing acoustic guitar on “Desolation Row.” That experience got Dylan intrigued about Music City’s potential. Johnston, already hoping to make that happen, helped massage desire into reality, abandoning the first sessions for Blonde On Blonde in Manhattan for the quiet streets of Music Row.

Sanders has been interviewing the studio musicians from Blonde On Blonde for years, and he clearly did a comprehensive literature dive to put the sessions in context. Also, thanks to a previous Columbia bootleg volume (#12 covering 1965-66), Sanders was able to listen to vast amounts of studio banter amid the rehearsals and false starts. That dialogue “debunks a lot of the popular misconceptions about Dylan, that he didn’t care in the studio, that he was just one take and let’s get out of here,” Sanders told WMOT for The String. “No man, he cared. Some of those (songs) he’s going twenty takes just trying to get the tempo that he wants. That’s one thing I wanted to do. I wanted to set the record straight.”

The book was an ideal preparation to listen to More Blood, More Tracks, because it foregrounded the idea of Dylan as revisionist, editor and self-producer in my mind as I investigated the process behind my personal favorite Dylan album. Devotees of Blood On The Trackswill find the work tapes on the box set fascinating and sometimes baffling. There are no fewer than twelve takes on the gem “You’re Going To Make Me Lonesome When You Go,” and in most of them, they attempt the song as a country bounce. It’s frankly terrible, lacking any poignance. Other attempts are too slow and melodramatic, not to mention disorganized. All those cutting-room-floor rejects have a drummer keeping time, but the album version does not. It’s one of many examples of a genius engaging in the kind of trial and error we almost never get to witness. We hear a creator ranging in on his target without knowing what the target looks like and finding the mark.

As a young guy newly fascinated with roots music and songwriting, I didn’t have that luxury. Dylan’s songs arrived fully formed and fixed on records. The closest I could come to inhabiting the creation was to transcribe the lyrics from the spinning LPs, compile notebooks, learn the songs and perform them for whomever would listen. Before this awakening I’d heard Dylan like millions of others – as another artist on FM radio with a few interesting hits and a most unusual voice. The interpretive process though, considering the songs as whole structures and actually feeling those shapely words form in my mouth, was an elevation and exaltation. I began to see just how exceptional this artist was as his daring embrace of language dovetailed with my formal study of literature. As I started writing songs myself, Dylan offered an expansive invitation and a license to reach for something ambitious. My background and schooling lent me the parallel mandate to revise and edit with as much passion as I drafted. I harbored no doubts that Dylan re-wrote and rejected and crafted and struggled like a mere mortal human being. But it’s energizing all these years later to hear the evidence first hand and know for sure.